Voices in the Wilderness

artists in the U.S. Forest service

It was a real privilege in 2014 to be chosen for one of the spots with the Voices of the Wilderness Artist in Residence program, run by the U.S. Forest Service. It seems a bit incredible they have this program and it's certainly in no small part due to the work of Barbara Lydon, it's organizer and champion. There's this great history of artists in US National Parks. It was artists, in fact, that inspired the protection and creation of the first U.S. National Park. Brought before Congress, it was the paintings of Thomas Moran and the large scale photographs of William Jackson that showed politicians the incredible landscape of the American west, justifying protection over exploitation. In 1872 , U.S. Congress passed a bill protecting the area of Yellowstone, initiating a global legacy of park systems. Moran's paintings still hang in Washington, both in Congress and in the White House. Capturing the essence and importance of the National Parks and the work that the staff and volunteers do to protect them is just as important today as it was in the mid 19th century. The Voices of the Wilderness residency aims to continue the tradition and I'm quite proud to be part of that.

Loading the Lazy Otter in Whittier, AK. I stopped painting the bags as there were a lot of bags. Our kayaks were the three yellow ones up top. The rest were for at trip for teachers run by Alaskan Geographic. Alone, we were rigged for almost two weeks of patrolling.

Offloading The Lazy Otter landing boat at Pakenham Point in Prince William Sound. Two standard sea kayaks for Barbara and Trace, one XL kayak for the artist and all his stuff, six bear barrels of food, two tents, thermarests, sleeping bags, rain gear, fuel, paddling jackets, tarps, weeding tools, garbage bags, radios, etc etc. A lot of gear.

“An area of wilderness is further defined to mean in this Act an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its primeval character and influence, without permanent improvements or human habitation, which is protected and managed so as to [...] have outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation...”

The Wilds according to .Gov

The United States has Congressionally designated and protected Wilderness Areas. They are areas set aside for recreation but having as little human infrastructure as possible; there can be no roads, no permanent campsites, no landing pads, forestry or mining. The Wilderness Act of 1964 is this great forward looking legislation that really seems to anticipate the needs of future generations. In explaining Wilderness, it reads:

An area of wilderness is further defined to mean in this Act an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its primeval character and influence, without permanent improvements or human habitation, which is protected and managed so as to preserve its natural conditions and which (1) generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man's work substantially unnoticeable; (2) has outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation; (3) has at least five thousand acres of land or is of sufficient size as to make practicable its preservation and use in an unimpaired condition; and (4) may also contain ecological, geological, or other features of scientific, educational, scenic, or historical value.

I'm most in admiration of the "outstanding opportunities for solitude" part. Being Canadian, we have Crown land (technically owned by the Queen), but I'm just not sure we have analogous legislation that protects our spiritual and civic right to an unsoiled version of it. That's important.

Our little bit of Wilderness for the week was Harriman Fjord, part of Prince William Sound and the Chugach National Forest, about 90 minutes south of Anchorage in Alaska. While not a Congressionally designated Wilderness Area, the U.S. Forest Service Rangers based in Girdwood were fairly determined to manage it exactly as such in the hopes that one day it would be completely protected.

Through the water of Prince William Sound towards Herriman Fjord.

The thing that struck me the most about the Chugach region is the way the landscape expresses time. There's this incredible sense in it of time being compressed; a feeling of geological and ecological recency. You can read the land and see it's life story: a glacier carved that valley, a recent avalanche flattened that forest, an earthquake raised that shore line, the rising sea poisoned those trees, those bushes are the first to grow there in over a million years. It all seems like it happened just a few days ago and in the grand scheme of things it really did. You are only a visitor who has just arrived on this land, your host. As with any host, there is a feeling of a great, clear, quiet understanding between you and it. Your host tells you where you can go and where you can't. It shows its wisdom and, if you're listening, it feels like it will be imparted to you if you're patient and polite. Those of us who live in the environment that we have built for ourselves - the roads and the strip malls - lose the clarity of that discourse with the land. We become largely detached from it, its lines are obscured by our constructions and scarred over by our abuse. For the vast majority of us the land we live on stops telling us things because, for the most part, we stop listening. Its voice gets drowned out by all our noise.

My first painting in the field, sitting on a house-sized boulder at the foot of Coxe glacier and looking across the fjord to Cascade glacier. An incredible landscape doesn't seem like it would be too great a detriment to painting. But for me, someone who makes his living dealing in details, trying not to show everything was so difficult! The landscape was so enormous that I would sit down and start painting and, before long, would realize that my subject simply wasn't going to fit in my little spiral bound sketchbook. In this image I was trying to capture the shadows of the clouds drifting across the mountainside. Of note: Barry glacier, which, 10 years ago, would have run into this scene from the right and covered the little island at the foot of Cascade, has receded almost a kilometer in that time. Climate change is a very real thing and very noticeable in Alaska.

Alaska came to represent this new baseline for what I personally call "Wilderness". If you were someone who grew up in a city or suburban environment, your baseline might be the local park. Parks have squirrels, trees, grass and some underbrush. If you come out at night you might find the odd skunk or possum or raccoon. There's brush for songbirds and maybe a pond for resident or migrating waterfowl, but there isn't really enough. I grew up able to access a little more than a city park, so for me a city park is not very close to the source, to what we should call "Wilderness". The baseline for what many people call wilderness is not very wild. It is still largely a constructed thing. Our desire paths course through it and carve it up; there's a garbage can up ahead for you to put your coffee cup in and a bench to sit on. We hope that nature will share it , but really we built it for us. For others like myself, wilderness is the forested edge of farm fields or the lakes of cottage and summer camp country. Maybe it's the forestry block we worked summers on, planting trees during university. But for most of us we become accustomed to seeing man-made things in our wilderness: campsites, fire pits, roads and paths with their painted blazes so you don't lose your way; the odd discarded bit that someone might have accidentally or deliberately left there, or even the boot prints on a muddy trail. These things and our experiences in them standardize what we call Wilderness. But Alaska is different. Despite how accessible much of the Chugach National Forest is to Anchorage residents and cruise ship tourists, it still manages to dramatically lower that precious baseline defining what Wilderness is. At least it certainly did for me.

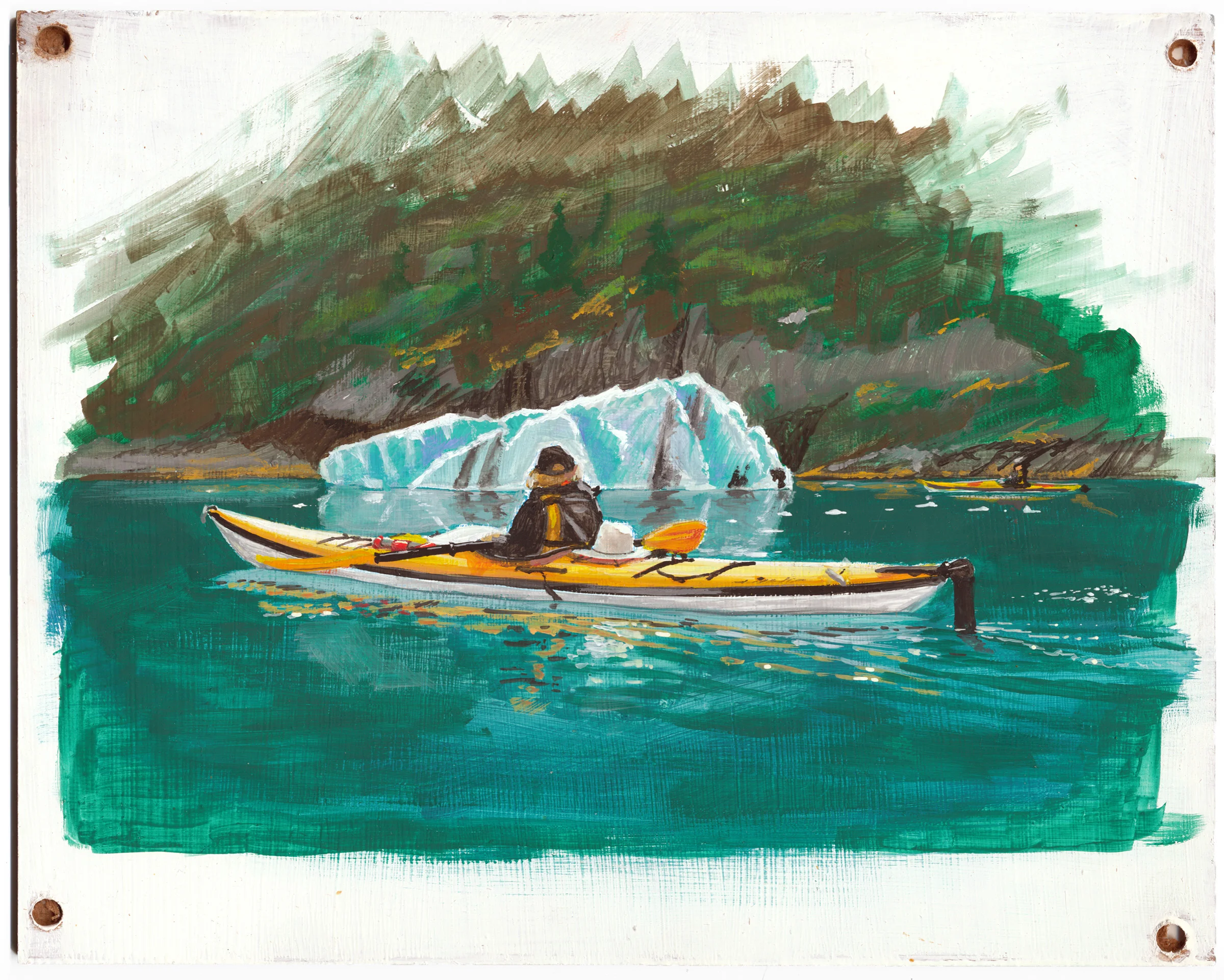

On our way to Coxe glacier, Barbara and Trace check out a small iceberg calved from a glacier. It was fun picking our way through chunks of ice; some just little bits, others the size of houses. Beautiful, cold, deep turquoise water. Casein on gessoed panel. Co-ordinates: 61.113015, -148.140475

On our way to Harriman Glacier, we tucked ourselves into a little cove to take a little break from paddling. We rafted up like otters and bobbed about, eating our lunch out of the wind and rain. We always kept some snacks handy in the cockpit for a break from paddling. There's something amazing about eating crispy food like crackers when it's raining. Crispiness just tastes better!

As a Leave No Trace area, part of our job as Rangers on our patrol was to clean up known campsites and pack out the refuse. We picked up the odd lost tent peg. I found a zipper pull in the grass - all of two square centimeters of black nylon. We sunk a cinderblock that some hunters had used as a seat or a boat anchor at their bear camp. It was too heavy to pack out on a sea-kayak so we made the executive decision to simply sink it out in the deep water. From the grass at View Beach, seemingly pristine, we pulled two garbage bags full of dandelions. They flourish where people pitched tents. They don't have a particular affinity for tent pads. In fact, they aren't even native to Alaska. Their seeds come in on the tents and boots of visitors, and land right there, miles from anything. When the landscape was as wild and perfect as it was, all of these foreign items were easy to spot. They lit up and stuck out like they were neon - even the black nylon zipper pull.

We also monitored human traffic in the area. There aren't any roads, but a few sailboats, bush planes and helicopters do pass through and over the area. We actually camped on a beach and looked for signs of helicopter skids landing in the gravel field of the retreating glacier. We even looked for footprints, evidence that tourists had climbed out of a helicopter and stood on the freshly exposed gravel. They were foreign to that environment and as such they stood out. Each time a boat or aircraft flew over, we documented it, tried to get the tail number and included a comment about how it made us feel. This formed a sort of a qualitative report on the state of the wilderness that the Rangers were intent on protecting.

Once the weather cleared, the gravel field at the face of Harriman glacier was home for a few days. The tides are very high in the fjord so we parked our boats and made camp quite far from the water. Doubly smart since you never know when the glacier would calf, sending large waves your way. The winds off the glacier made for some cold camping (and bathing!), but also made for some great kite flying. Tied to a kayak, Pocket Kite stayed up all day. Here Barbara kicked back after a day of rangering.

It's a beautiful but intimidating landscape. You feel small in it. We camped one evening at the foot of a boulder field. A little walk uphill revealed how recently those boulders had been deposited there as they intermixed with large trees. All the trees had been smashed like twigs. Paddling out the next day, we could see that the boulders had been part of a landslide off of a hanging valley and cliff above. A reminder that you don't want to be there when geology happens. But geology is always happening. The awesome quiet is regularly punctuated by the thunder of distant avalanches and slides, and the calving of glaciers. If you're near the water you have to keep an eye out for the swells that arrive a few minutes after the calving.

The field of gravel deposited by the retreating terrestrial part of Harriman Glacier was vast as this 180 degree panorama demonstrates. The face of the glacier is almost 2km wide.

Our time at Harriman was spent divided up with me doing some painting while Trace and Barbara visited a couple of other spots in the area that people were reported to have camped. They cleaned up what they found, weeded invasives, and took some notes as per how much impact the campers' visits actually had on those places. They drew maps of where firepits, where tents had obviously been pitched and where latrine areas had been, all for future reference to see how these sights change over time. We logged the coming and going of aircraft and marine craft, monitored any radio traffic we could.

Being dive bombed by angry seagulls while painting at Herriman glacier.

Days were deceptively long as the sun never really set. We would finish cleaning up from dinner and then look at our watches only to discover it was after 9pm with full bright daylight like it was 5pm at lower latitudes. I spent some time exploring, taking pictures and video and scrambling up the slop next to the glacier. My quick paintings tried to capture the cold iridescent blue of the glacial ice that you have to see to believe - all while being dive-bombed by gulls. We walked cautiously trying to determine if there was a nest that we were near or some eggs that we might carelessly tread on, but there were none that we could find, just very territorial gulls.

The face of Harriman Glacier is so tough to paint! I always have trouble with the greens of forests at best of times, but couple the greens of the hillside beyond and the iridescent blues of the ice was pretty difficult. Casein on paper. Co-ordinates: 60°58'12.0"N 148°25'36.3"W

Sketch of USFS Ranger Barbara Lydon standing on a high point to get a weather report on the radio.

After three days at the face of Harriman, we packed up the camp and the kayaks and headed back down the fjord to View Beach. It was a prefect day on the water; good sun, no wind. The calm and quiet was incredible. You could tune in and listen to everything in the fjord: the birds on the north side, waterfalls on the south side, the glaciers cracking and calving. Unfortunately, the calm would not last. Once at View, we were able to get a weather report relayed to us over the radio that indicated a serious Pacific storm was headed our way. We were faced with the choice of staying put and weathering the storm (could be interesting) or paddling back to Coxe and Barry Glaciers, meeting up with the group of teachers and hitching a ride out to Whittier on their boat. We opted for safety and the ride out. As Barbara said: it's always better to be left wanting a bit more of a good thing than regretting a choice which, she advised, we might certainly do if we stay put. So while Trace and Barbara tidied up View Beach, I got to sit on a grassy hummock with the best view in the world, doing one last watercolour painting before paddling out to our meeting point.

View Beach across to Surprise Glacier. The fjord was like glass and the silence was incredible. If we could have stayed out for another few days, I don't think I would have ever tired of seeing this. Watercolour. Co-ordinates: 61°02'08.9"N 148°18'48.7"W

Time lapse video shot over night of Cascade Glacier in Harriman Fjord. The incoming storm was preceded by the rain you can see in this sequence. 61°07'05.1"N 148°08'05.8"W