For the love of sternums

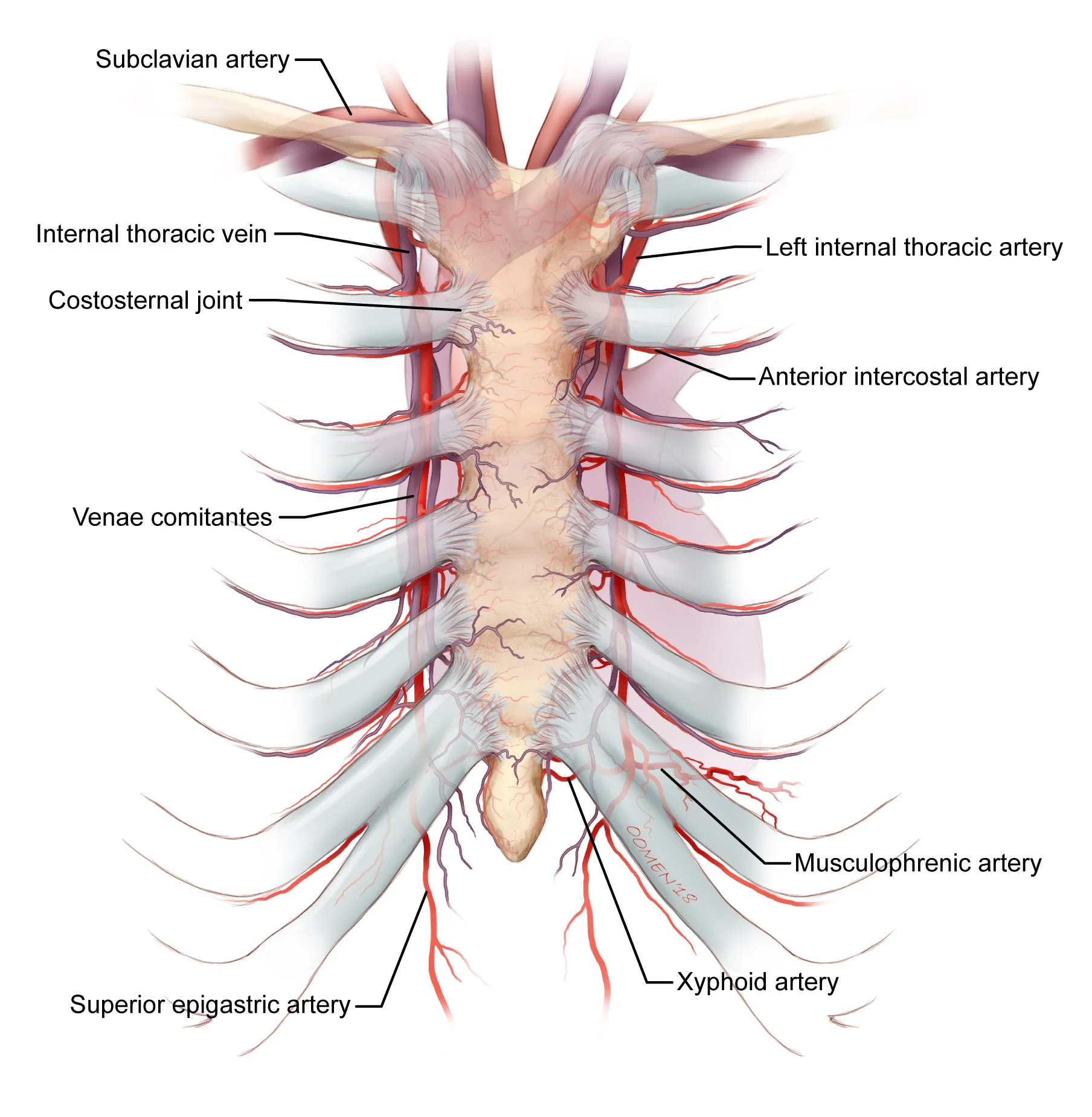

General sternum anatomy. Copyright 2018 Oomen/Gandhi

Over the summer I helped a local orthopaedic surgeon with his labour of love. I came to know Dr H when I was working in Anatomy as he was requesting we collect cadaveric sternum samples for him to examine, both from a morphological perspective, and for evidence of non-union were they to have wire encirclage from sternotomy. Dr H was investigating why, while the rest of orthopaedic surgery had advanced in terms of tools and techniques, this one aspect of it - usually performed by a thoracic or cardiac surgeon - virtually had not. He thinks he has a solution. But before he can present that he has to present the problem, so he recruited me to help him by drafting a series of illustrations, three of which are shown here.

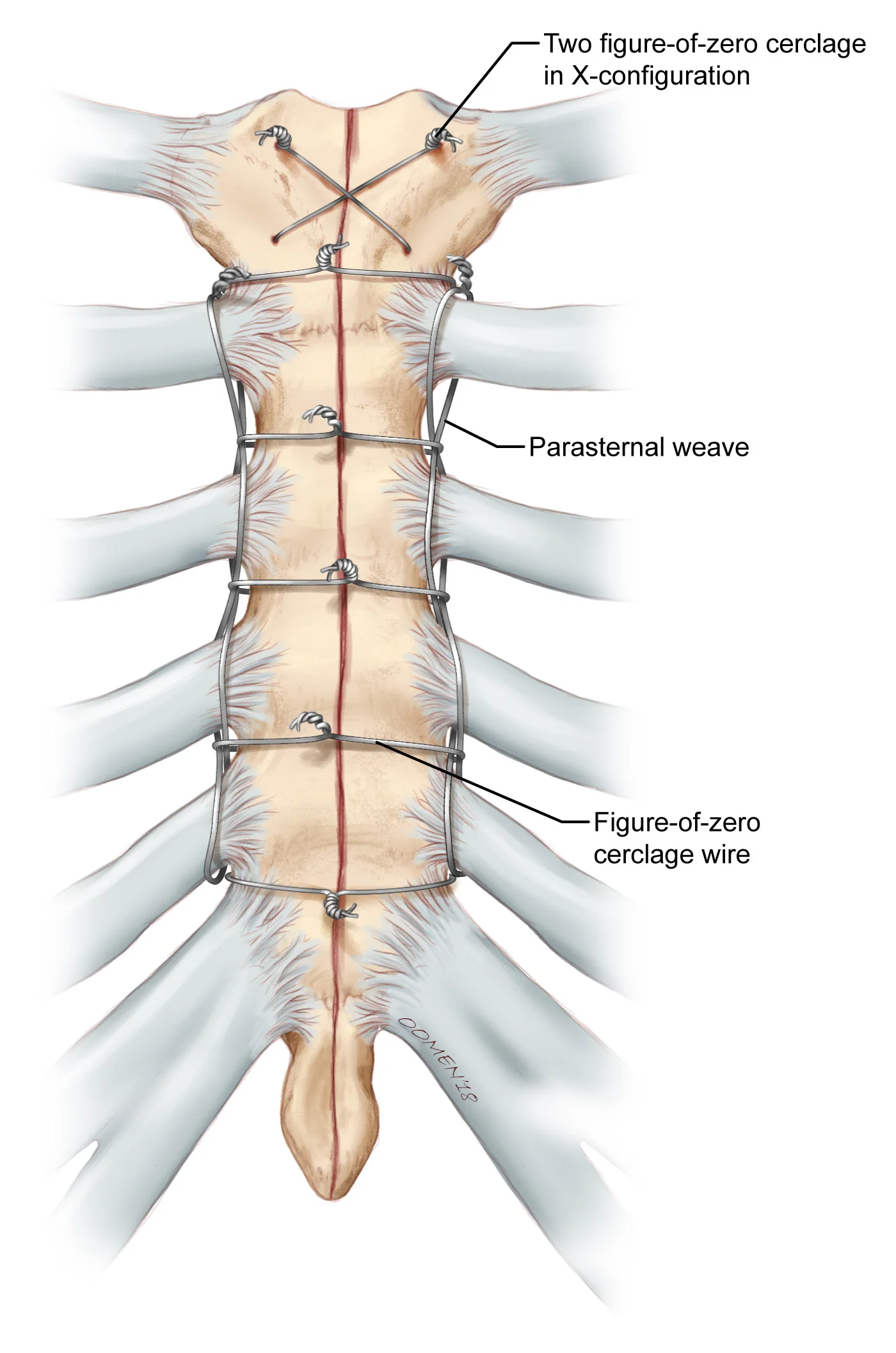

Parasternal wire weave for binding sternum post sternotomy. Copyright 2018 Oomen/Gandhi

For background, a sternotomy is the cutting in half of the sternum to access the pericardium and heart, and is required for major cardiovascular procedures such as valve repair and replacement, coronary artery bypass graft etc. It’s about as serious as surgery gets. Due to the large scar left afterwards up the center of their chest, it’s recipients become reluctant members of the “zipper club”. The sternum is cut with a fine reciprocating saw, usually up the center, but occasionally off-center (parasagitally) depending on the blood supply to it. The two halves are pulled apart and held open for access to the heart by a large thoracic retractor. This part is OK, ribs, at least the cartilagenous parts, are flexible and, despite advances in minimal access cardiac surgery, sternotomy is still a necessary procedure. When all is done the tissue enveloping the heart, the pericardium, is sutured closed again. The retractor is removed, and the two halves of the sternum are drawn back and tied tightly together with thin stainless steel wire. The patient is sent to post-op recovery and a couple of days later, as long as everything goes well, they’re sent home…with strict instructions not to cough, sneeze, strain, or lift anything. For months. Any of those movements might just pull the two halves of the sternum apart before the bone has a chance to mend. And this is part of the problem: it doesn’t always mend. Non-union, where the two halves fail to heal and grow back together, occurs in about 2-3% of all patients. Any movement of the pectoral girdle; any cough or sneeze or excessive abdominal strain, literally, pulls the sternal halves apart.

Allow me an analogy. A ship has a keel: a strong girder or beam down the midline, along the bottom of it’s hull. It’s the first thing laid down when the ship is built and the rest of the ship is constructed up from it and around it. It is at the core of it’s structure. In a good ship, that keel is strong with just a slight flex in it to absorb heavy seas, loads and impacts. As sailing ships age that keel becomes “hogged”: where the bow and stern sections, with less bouyancy, sag towards the waterline as the keel becomes overly flexible and loses its rigidity. A sailing ship needs the keel to be strong and straight in order to transfer the pressure of the sails into the water. Alternatively, modern torpedoes are designed not to strike the ship and punch through the hull, but to explode right beneath the keel, breaking it and the ship in half. You break the keel, you break the ship.

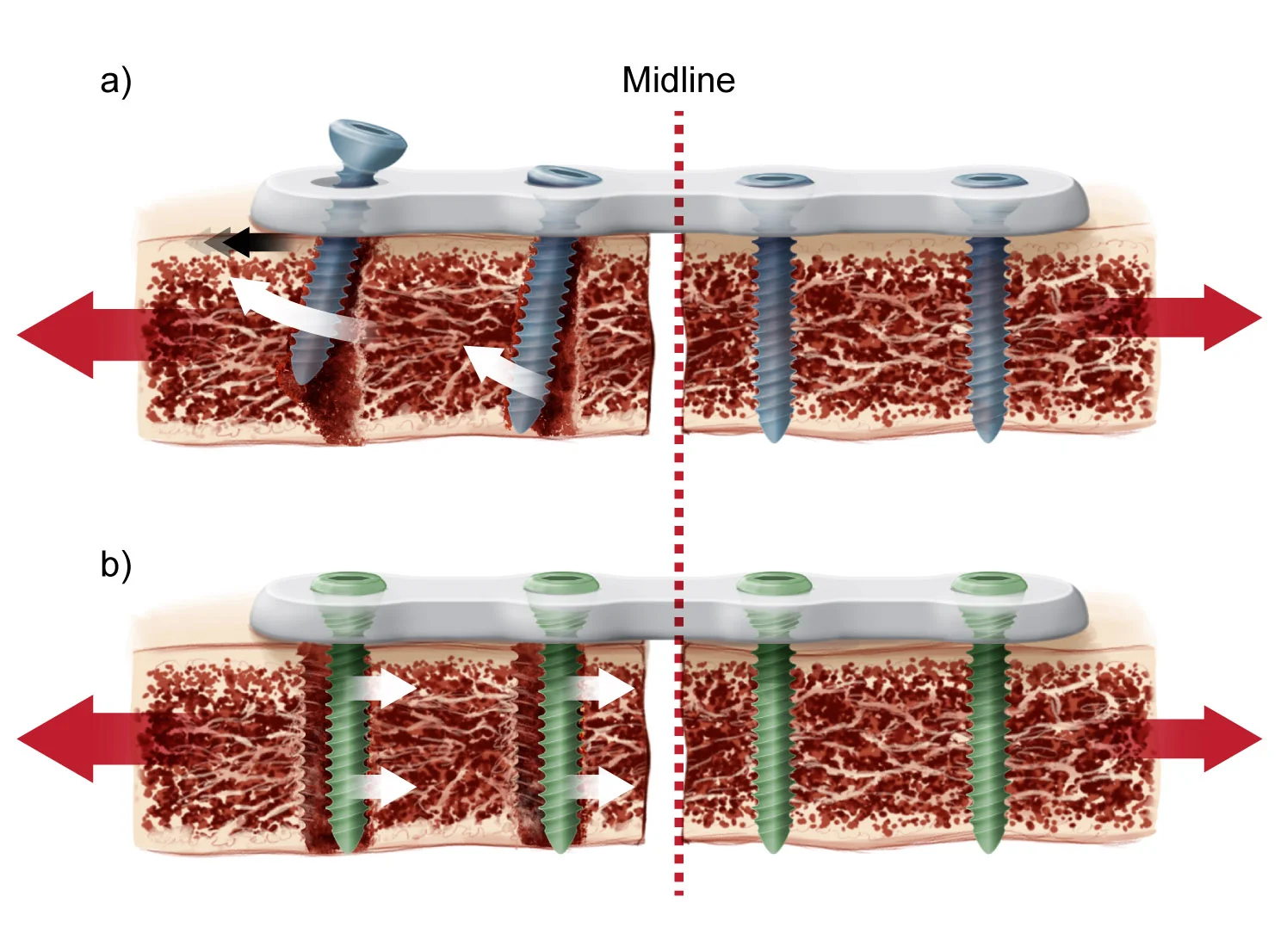

Non-locking vs Locking screw/plate tear out patterns. Copyright 2018 Oomen/Gandhi

The same can be said of the human body: you brake the sternum; at least until it heals, you break the skeleton. Daily, there is not a force that the human body encounters that does not go through the sternum in some way; most pulling one half of a cut sternum away from the other. Any movement that is unilateral (are you right handed or left?) will create both up-down and front-back shearing in addition to the distracting force between halves. Even a patients own weight - the mass of their shoulders, arms or breasts - can pull the sternum apart while lying on their back, at rest. And coughing or sneezing…well...think of the torpedo metaphor. This is actually a really fascinating and serious biomechanical problem, one I wish I had recognized when I was teaching anatomy. It has massive implications.

Probably for as long as sternotomies have been performed, the two halves have been tied back together with thin stainless steel wire, wrapped and twisted around the halves in various manners and techniques like binder twine. With few exceptions and changes, we have been using the same tools for 70 years. Beyond it’s potential to clamp down on internal thoracic arteries, veins and collaterals, disrupting blood flow, the real trouble with wire is that with every movement it bites into the thin cortical bone of the sternum. With every bite the wire, in turn, loses some of the tension required to hold the sternum together. With less tension, the two halves become more mobile and the less likely they are to mend. Screws and plates aren’t a whole lot better as, in some cases, there just isn’t enough strong cortical bone for them to anchor into. The screws can also erode the bone with each push and pull cycle. There’s even a glue to stick the two halves together, but that seems to form an impermeable barrier between them, potentially preventing any biochemical communication across the wound so they still don’t heal. In the worst cases of non-union the sternum necroses, the thin skin over it ulcerates and conditions deteriorate. Dr H estimates that, given the number of sternotomies performed each year in North America, on average 2 people per day die from non-union.

It’s the classic “We’ve always done it this way” explanation. Time for some innovation, I think.