The Process (part 1)

Everyone has a process that they go through more or less every time. When it's work, a formula helps get it done. Sometimes it's good to abandon the formula to shake things up and bust out of a rut, make things less work and more art. Lately I've been swamped with work so I'm a little dependent on the formula to help me get it all done reasonably well in the time allowed. Freelancing, at least for me, is living every self employment cliche and it isn't all working in lovely coffee shops watching the world go by, never you even mind working outside in a lounge chair under palm fronds in Bali. No Sir/Ma'am. Make hay when the sun shines? When it rains it pours? Fun to say, not so fun to live. I don't get paid until I'm done making that hay and catching all the rain I can. So it's not surprising that when I'm swamped, I find the quality of my work goes down (just what my clients want to read). There's little to inspire me and make me think of how I do something, it's just 'git er done'. The cliches keep coming. At the moment, when I'm a fulltime freelancer and consultant this gets harder.

I used to teach this great little undergraduate course in the Faculty of Health Sciences at McMaster University on scientific/medical illustration, and in order to teach every week I was forced to think about how I did what I did so I could share it with others. It was very introspective and I really think it made me better at illustrating. I miss that. So in an effort to add - or subtract - a little inspiration from this rainy, sunshiney, haymaking period, I'm going to write about my process.

Enter Dr S. Lets keep this relatively anonymous for the time being. Dr S is a Toronto based cardiovascular surgeon-scientist. By all accounts he's excellent at what he does, and what he does is operate by day and do cardiovascular research by day and night. He is what we would call in my family with suitable Irish understatement "quite the going concern". Aside from my grade 4 teacher, Dr S was the first person to hire me to make medical illustrations. He is my oldest client. We've certainly had our ups and downs, but generally I think ours has been a mutually beneficial relationship. I enjoy seeing what he's up to and I think he enjoys what I come up with.

Dr S is currently investigating the role of Sodium-Hydrogen exchange inhibitors in managing heart failure due to diabetes, and is planning on publishing an upcoming paper about it with accompanying talks. He has a PhD in pharmacology, so he does this. Frequently. Usually after some time, I get summoned and he explains the concept to me. He usually has some idea in mind as per how or what the images need to show. Often there's some chicken scratchy, back-o-the-napkin kind of drawings for me to decipher, and he gives me a few papers or key reference images that, up to this point are the state of the art in communicating the concepts he discussing. He too has a process and I'm glad for it. Some researchers just send me a paper, ask me to read it and then ask me to illustrate it, and then I'm stuck trying to figure out just what part. I don't mind that kind of leeway, but I'm glad Dr. S has learned to play Art Director. From there I come up with very rough initial sketches and generate questions as I think about them, send them on and see what comes back. Then we discuss.

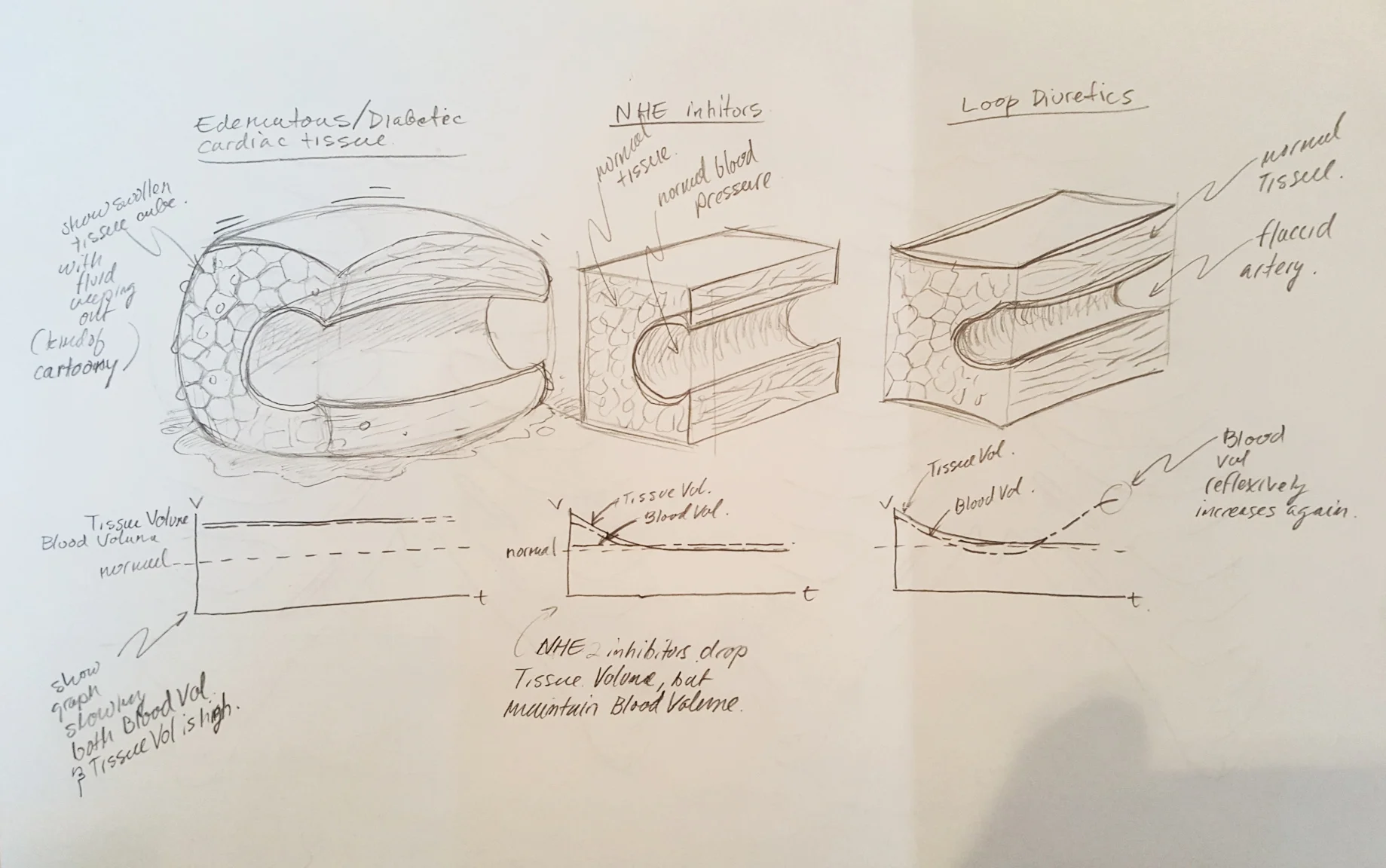

These are bad photos of those sketches. In the first image we're supposed to compare the diabetic failing heart and glomerulus with the same tissue when using NHE inhibitors. The hearts of each will have insets showing break down of extra cellular matrix, granular inflammatory infiltration etc. The second image will compare fluid tension in body tissue (edema) and blood (blood pressure) by showing a block of generic edematous tissue and comparing it with the same tissue using standard loop diuretics and NHE inhibitors. The images should show the changes in the tissue with each and show a little graph showing the effects of each agent on tissue volume and blood volume/pressure. Lastly is an image showing the mechanism by which NHE inhibitors work on the failing diabetic heart.

This was the first sketch of the first image contrasting the diabetic heart and glomerulus. "Disaster heart and glomerulus" at the top, and the heart and glomerulus with NHE inhibitors at work, all the disasterous effects of diabetes slightly ameliorated. The squiggly line notes are just illustration notes of what I'm trying to show and am usually not able to geven the crudeness of the initial sketch.

The second sketch of the second image shows the effects of NHE inhibitors on tissue fluid volume and blood volume when compared with standard loop diuretics. The image at furthest left shows the tissue during heart failure. The problem: how to do you show systemic edema.

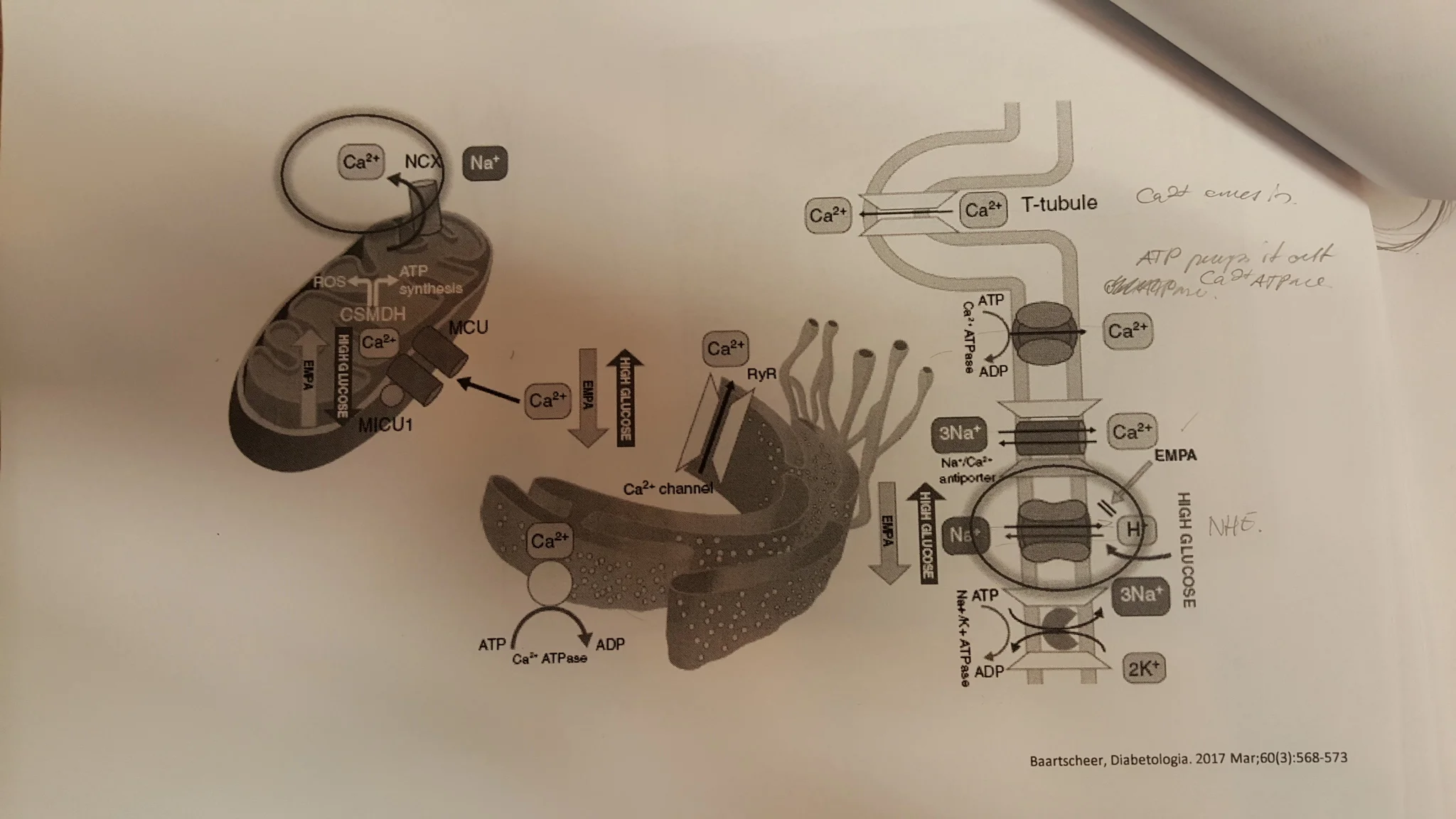

And lastly, this is a reference image of the mechanism of action of NHE inhibitors ("EMPA" in this image). It somehow shows the mitochondria inside a cardiomyocyte and its sarcoplasmic reticulum. Can you figure it out? I can't. Because researchers make indecipherable images like this, I have a job.

With respect to this last image, the mechanism of action, I don't actually understand what I'm looking at. I mean, what comes first? Reading from left to right you would think it would be something to do with Ca2+ and Na+ in the mitochondria. Then is that endoplasmic reticulum with some odd marine life strapped to the top of it? Then the classic blobs as transporters. What comes first here? Then what happens? What's the story?

Here's a tip: an illustration has a job to do, and it needs to be able to do it when you're not around to explain it. Sure captions can help, but ideally a really good illustration explains everything itself on its own. It can't always be perfect, but this is a good thing to strive for, a bit like rearing a child. Eventually you want that child to be independent, be able to stand up for itself, explain itself, be articulate, go out into the world and be trusted by others. And, since you won't always be there explain to its behavior, it had better be crisp, clear and well mannered.

You don't ever want people to look at your image and wonder about your design and illustrative skills any more than you want people to interact with your child and be left wondering about your parenting skills.

See the next steps in the next post.